Episode 2: The French Flag: The Tricolour

Fallen tyrants. New republics. And radical ideas like liberty, equality, and fraternity. This is the history of the Tricolour: the three-color revolutionary flag of republican France.

References

The Revolutions Podcast, Season 3 Episode 54. https://www.revolutionspodcast.com/2015/09/354-the-empire.html

“Ancient Symbol Fleur-de-lis: It’s Meaning and History Explained.” Ancient Pages. http://www.ancientpages.com/2016/10/10/ancient-symbol-fleur-de-lis-its-meaning-and-history-explained/

“History of the French flag.” France this Way. https://www.francethisway.com/info/franceflag-history.php

“History of the French flag.” Société Française de Vexillogie. https://drapeaux-sfv.org/flags-of-france/History-of-the-french-flag.

“How Did the French Flag Come To Be?” World Atlas. https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/what-do-the-colors-of-the-french-flag-mean.html

“Hundred Years’ War.” History Channel. August 21, 2018. https://www.history.com/topics/middle-ages/hundred-years-war

“Reign of Terror: 1793-1794.” Marie Antoinette and the French Revolution. September 13, 2006 PBS. https://www.pbs.org/marieantoinette/timeline/reign.html

“The Committee of Public Safety.” Alpha History. https://alphahistory.com/frenchrevolution/committee-of-public-safety/

“The French Flag.” France Diplomatie Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs. https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/en/coming-to-france/france-facts/symbols-of-the-republic/article/the-french-flag.

“The Oriflamme.” Luminarium: Encyclopedia Project. http://www.luminarium.org/encyclopedia/oriflamme.htm

“The Reign of Terror.” Lumen. https://courses.lumenlearning.com/boundless-worldhistory/chapter/the-reign-of-terror/

Frome, Carol. “The Tricolor French Flag.” Flag Blog. https://flags.me/2009/05/05/the-tricolor-french-flag/

Howard, Holly. “The Fascinating History Behind the French Flag.” February 5, 2018. Culture Trip. https://theculturetrip.com/europe/france/articles/fascinating-history-behind-french-flag/

Marshall, Tim. “A Flag Worth Dying For: The Power and Politics of National Symbols.” Scribner: New York, NY. June 2018.

Rischey, Tom. “The Reign of Terror: Part 1 of 2.” YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IpYdbhpRDqQ

Sache, Ivan. “Kingdom of France: The oriflamme (Middle Ages).” August 10, 2017. CRW Flags. https://www.crwflags.com/fotw/flags/fr_orif.html

Smith, Whitney. “Flag of France.” Encyclopaedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/flag-of-France

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Louis VII.” https://www.britannica.com/biography/Louis-VII

Music

“Fake French” by Le Tigre”

Source: FreeMusicArchive.org

“Night Owl” by Broke for Free

Source: FreeMusicArchive.org

“Something Elated” by Broke for Free

Source: FreeMusicArchive.org

“Drop of Water in the Ocean” by Broke for Free

Source: FreeMusicArchive.org

Season 1, Episode 2: The Tricolour

Show Transcript

This is Why the Flag, the show that explores the stories behind the flags, and how these symbols impact our world, our histories, and ourselves.

In the first episode, I explored how the history of flags are stories that are often written in blood. And too often, it's the blood of the poor, the slaves and the soldiers, the commoners, those unlucky masses who just happen to be stuck in the wrong place and the wrong time. Last time, I discussed the three Roman standards lost to the Germanic tribes during the horror that was the Battle of Teutoborg Forest, a battle of tribal revenge on an encroaching Roman empire that cost the lives of nameless thousands. And as you know from last time, the Roman response to the loss of their flags was devastating – Germanicus launched scorched earth campaign into Germania, cutting down anyone and everyone who stood in their way, leading to decades and centuries of bloodshed.

But the history of flags can also the stories of fallen tyrants, new republics, and radical new ideas like liberty, equality, and fraternity. And that's what this episode is about. This is the story of the Tricolour, the three-color revolutionary flag of republican France.

Blue, white, and red – these were the colors worn on the cockades of French revolutionaries who risked their lives to overthrow the tyranny of King Louis XVI and the Bourbon Dynasty in the name of republican ideals. Today, these colors represent ideas like individual freedom, representative democracy, and The Declaration of the Rights of Man. But how we got there, as history often shows us, is a far different story than these high-minded ideals may portend. Yes, today, the French Tricolour represents a nation with one of the world's oldest and longest-lasting democratic traditions. However, we cannot ignore the fact that these are the same colors that flew silently as the guillotine took the heads of tens of thousands of citizens during the French Revolution's infamous Reign of Terror.

The Tricolour and the sordid history of the French Revolution are inescapably connected, but this is not going to be an episode about just those events, nor will we dive into the complexities that are the history of the Revolution. For that in-depth narrative, I cannot recommend enough that you listen to one of my all-time favorite shows, season 3 of the Revolutions Podcast. I'll leave a link to that podcast in the show notes.

So, where do we begin? Well, in my opinion, to really get to the heart of the Tricolour, we have to go beyond the French Revolution and take a wide-angle lens look at that nation's history. We will try to answer: what do blue, white, and red really mean and where did they come? How did the French flag evolve from its medieval origins as an orange-red flame to this bold and modern tri-colored banner – and how are those histories connected? And finally, how is it possible that an iconic symbol of peace and freedom was in fact conceived in militant revolution, born on a battlefield, and raised in the blood that filled the streets of Paris and almost every other major city in France? I'll warn you now; this show can get a little dark. But the history of flags is known to be a bit colorful.

A quick disclaimer before we begin, I need to warn all my French and Francophile listeners that this is going to be a controversial episode, mainly because the thesis I present about the origins of the French colors have been hotly debated for centuries – and are even disputed up until this day. But I will offer as many of these competing ideas as I can in the time that I have. Also, keep in mind that I am not a historian nor an expert on France, but with that said, I am going to give historical context to these colors in a good faith effort to get to the core of the question at hand, why the flag? And in the case of this episode, why the Tricolour?

Each color on the flag has roots that are deeply engrained in the history and collective memory of the French people. What each color represents, however, is not so black and white. The meanings of the colors, both individually and collectively, have grown, evolved, and changed in fashion with the political climate and the cultural zeitgeist of the era. In fact, to make it even more difficult to define the Tricolour accurately, it happens that each color on the flag has held more than one meaning at the same time – and there are even competing narratives to where those meanings originated. So, if you think you've wrapped your head around that concept, it's time to follow me down the rabbit hole – the trou de lapin – where we'll first cover the evolution of the French flag, and discuss competing definitions of the three colors. And to kick off the story, let's begin with the Capetians and the Oriflamme of St. Denis.

The House of Capet – known as the Capetians – were the dynastic rulers of the Kingdom of France for more than 340 years during the middle ages. They snuffed out in the year 1328 with the death of Charles IV, the virulently anti-Jewish king, who left no male heir. The battle standard of the Capetians – a standard being a proto-flag, if you recall from episode 1 – was a flag called the Oriflamme, the golden flame. The Oriflamme was the personal flag of Emperor Charlemagne, the medieval King of the Franks (that is, the French) and Emperor of the Romans – and this Oriflamme was said to be gifted to him by the Pope in the late 800s. You can see what the Oriflamme looks like in the show notes on our website, but to describe it for you here, picture the Oriflamme as long, orange-red banner, sometimes displaying a golden sun, and at other times the name of the martyred patron saint of Paris, St. Denis. Now, St. Denis was the bishop of Paris in the 3rd Century, who was beheaded by the Romans for his role in converting many of the local pagans. Legend has it that the red color of the Oriflamme and the long-pointed spikes which flew at its end alludes to it having been dipped in the blood of the beheaded St. Denis. Whether ironic or funny or divinely inspired, the headless St. Denis is also the Catholic patron saint of headaches, which I guess is a more permanent remedy than Advil. And this being a show that covers French history, you can rest assured that he is not the only one who will lose his head by the end of the episode. But keep your head on your shoulders because you'll need it to remember the blood-red color of St. Denis on the Oriflamme because this red comes back in many interpretations of the red on the Tricolour.

The Oriflamme is said to have been first brought into battle in 1124 by King Louis le Gros, flown alongside the blue and gold fleur de lis, the royal banner of the King of France, and a flag that we'll get to shortly after this. The Oriflamme was a symbol of both heraldry and fear, because when this flag was marched into battle with the king, it meant that no quarter was to be given, and no mercy shown to the enemy. So important was this Oriflamme – this physical manifestation of God's guarantee that St. Denis was on their side in battle – that he who held it had to swear an oath to protect it with his life. I'm going to paraphrase a quote from The Standard History of the World, Vol. 4., this very oath:

"You swear and promise, on the precious body of Jesus Christ…and on the bodies of St. Denis …that you will loyally, in your own person, guard and govern the Oriflamme of our lord the king…that you will not abandon it for the fear of death or any other cause, but that you will in all things do your duty, as becomes a good and loyal knight, towards your sovereign and liege-lord."

I'm going to pause here for a second because this oath to the Oriflamme gets to the heart of the theme of this entire series. Here we're seeing men sworn to die to protect not a king, not a nation, not a family – but a flag, a mere symbol made from silk and cloth. I guess this means that, in a way, the flag becomes the king, becomes the nation, becomes the family. The flag, ordained by God, becomes more than a mere symbol, a mere collection of color and shape, but becomes the entire realm from heaven to earth – and that, as we see carried on by patriots today – that becomes more valuable than life itself.

Pre-dating the Hundred Years' War by more than two centuries, the Oriflamme is best known for the role it played then in battles between the English House of Plantagenet and the French House of Valois over which dynasty was the true heir to the Kingdom of France. While the Oriflamme was a totem believed to be ordained by God to ensure victory to the French, the flag proved them wrong because it was captured in two separate losing battles – the last of which was the Battle of Agincourt in 1415, presumably the final time that flag was flown. Some historians contend that the Oriflamme was raised as late as 1465, but I've read authors tell both accounts, so I'll leave that argument to them. But we do know for sure that, in keeping with their sacred oaths taken on the body of Christ himself, both of the flag's bearers in those battles gave their lives to protect the flag before it was taken from their hands.

We could have done a whole episode on just the Oriflamme because its story is so magnificent, and the history of its character in the Hundred Years War so bloody and profane. But as I mentioned, the quick takeaway from that story as it relates to the Tricolour is the red color of the blood of St. Denis.

After the break, we're going to jump into the banner of the Kingdom of France, the fleur de lis I mentioned earlier, and the symbol that outlived the Oriflamme and ruled the kingdom from the middle ages all the way through to the French Revolution. And in many cases, this symbol still in use today – from the flag of Quebec to the helmets of the New Orleans Saints. We'll discuss the fleur de lis right this.

BREAK

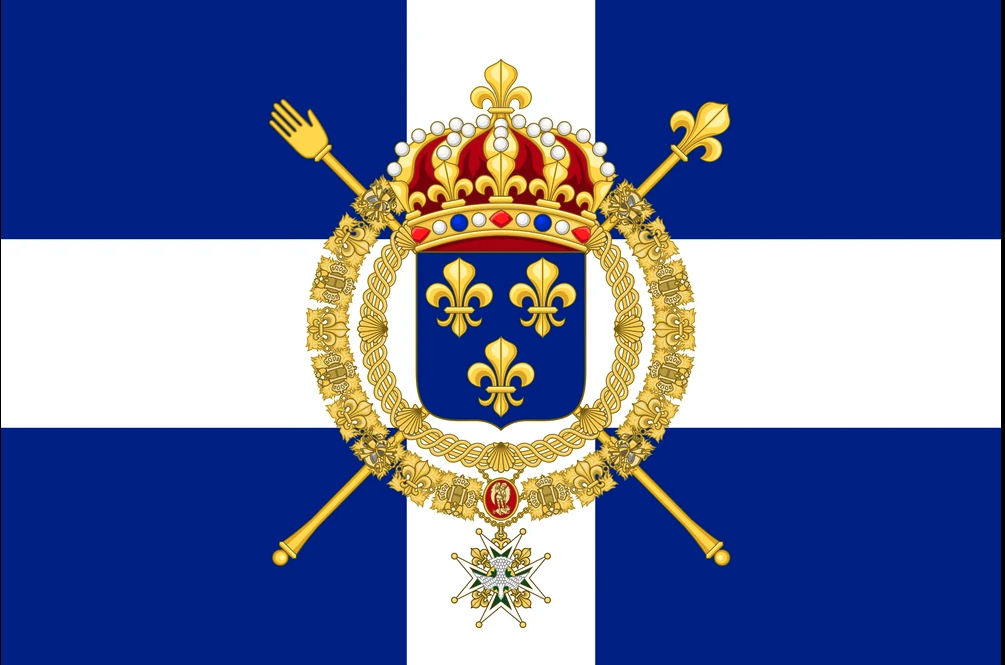

King Louis VII, known to history as Louis the Younger, was a French monarch who ruled the Franks for the greater part of the 12th Century. While his legacy includes such feats as the original construction of the Notre Dame in Paris, he is also the first king to bring the Banner of France – the golden fleur de lis on a blue background – with him into battle as he left for the Holy Land during the crusade in 1147. The fleur de lis pattern was originally worn during the coronation of the French kings, but Louis the Younger took this lily-flower emblem out from the court and into the world, marking it as his own and elevating it to the status of the royal symbol of the French Kingdom. And as I mentioned earlier, this flag was often flown alongside the Oriflamme until that banner fell for the final time.

Because of this past, the fleur de lis is most commonly associated with the French Kingdom. But in fact, its origins go back thousands of years. We'll touch on this very briefly now. The fleur de lis' lily flower design is an ancient emblem of royalty that spans Indo-European history, found as far away and as long ago as ancient India, in use during the Ksahtrap Dynasty nearly 2000 years ago. It has also been discovered on the helmets of the Scythian kings – the nomadic tribes who ruled the Pontic steppes of Eurasia roughly 2-300 years before Christ. Like I said, this will be very brief, because I want to get back to the story at hand. But it's interesting to note that this emblem has been in use by royalty throughout history, including the Babylonians, Romans, the ancient Indians, the Egyptians, and of course, the Franks. That said, let's back to France.

Legend has it that a golden lily flower was given to King Clovis I by the spirit of the Virgin Mary at his baptism in the year 496. As the first king to unite the Frankish tribes under a single sovereign in what is today France, this fleur de lis became the symbol of his purification upon being converted to the Christian faith. So holy is this lily, that it is said to be in the shape of the tears shed by Eve as she was cast from the Garden of Eden at the genesis of Creation. With the coronation of Clovis I in the 6th Century, the fleur de lis pattern placed on a royal blue background became the symbol of the French crown – and one that lasted for over 1000 years.

In 1376, King Charles V commanded that the pattern on Banner of France be reduced to carry only three golden fleur de lis on a blue ground. This way, in his eyes, he was able to legitimize France as the true Catholic Kingdom, with the three fleur de lis paying homage to the Holy Trinity – that is, the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. From that time on, this flag would become known as the France Modern.

So, from the royal banner to the France Modern, it can be speculated that this is where the Tricolour gets its regal blue, known ironically during and after the revolution, as the King's Blue. Over time, as these colors were ingrained into French history, the St. Denis red of the Oriflamme and the royal King's Blue of the France Modern merged, becoming the two colors to represent Paris, the capital of France and a historic seat of French power. To quickly touch on another theory of the blue, as I promised, it is said that it could also represent the patron saint of France, St. Martin of Tours.

Martin was a Roman cavalry officer stationed in Gaul – the ancient name for France – who converted to Christianity, turned on Rome and, when he became a bishop, persecuted and suppressed the followers of the local pagan religions. Nice guy. But the most often-told story of St. Martin, for which he is venerated, goes like this: Martin, the cavalry officer, was riding his horse through the city gates and was approached by a naked beggar. Because Martin was a pious dude, he cut his blue lamb's wool military cloak in two, clothing the man with his other half. That night he goes to bed and has a dream that this was no beggar at all, but Jesus Christ, and when he awoke, the cloak was miraculously back to its full form. Next thing you know, he converts to Christianity, opens a monastery, is named bishop of Tours in 371. Upon Martin's death, his burial place in France becomes a shrine. Decades later, King Clovis I – remember him? The first Frankish king – has his body exhumed, and low-and-behold, there was his cloak. The king took this cloak and flew it as a banner flag into battle, and from that day forward, the miracle of his blue cloak was legend. Therefore, we can reasonably assert that the blue in the Tricolour also comes from the tradition of the miracle of St. Martin's magic blue cloak.

As I mentioned earlier, there is no agreement to the true meaning of the red and the blue as they are represented on the Tricolour – and it becomes especially hard as the interpretations of these colors change with the politics and culture of the times, and meaning is even applied retroactively. However, the most logical conclusion about where the red and blue originate come from where we began the story – from the Oriflamme and the Banner of France, the two royal flags in continuous use until the mid-15th Century. And if you feel good about that, I am sorry, because the meanings of these colors will again change as we continue through the episode.

Now that we think we've covered the histories of the blue and red, the next question is, where did Tricolour get its white band?

Well, like I mentioned earlier, it depends on who you ask – and specifically when you ask it. But, historically speaking, the color white has been long associated with the Bourbon Dynasty since at least the late 17th and early 18th Centuries. Remember them? Between the time of the blue France Modern and the Tricolour of the French Revolution, a commonly used standard of the French royal family was a golden fluer de lis pattern laid across a white ground. In fact, even after the revolution during the brief restoration of the monarchy in 1814, the flag of France alternated between a pure white flag, a blue and gold fleur de lis on a white background, and the Bourbon Dynasty's blue and red fluer de lis coat of arms laid upon a bright white field. But the question is, how did white become part of the French collective memory? How and why did the Bourbon's adopt this color as their own?

A long-held belief is that the white is to symbolize the purity of the Virgin Mary – you'll remember her from earlier, when she presented the golden lily, or fleur de lis, to the first Frankish King, Clovis I. Interestingly, the gold fleur de lis on a white flag was also the royal standard of Joan of Arc, the 15th Century French heroine, who brought this flag to national prominence when she brought it into battle during the successful French siege of Orleans against the English in 1429. I found a great quote from Joan of Arc in one of my new favorite books and a powerful source on the subject, A Flag Worth Dying for by Tim Marshall. When she was on trial for heresy after being captured by the English-allied Burgundians in 1430, she describes the flag in her own words:

"I had a banner of which the field was sprinkled with lilies…it was white…there was written above it, I believe, Jesus Maria; it was fringed with silk."

The prosecutor slyly asks her next, "Which did you care for most, your banner or your sword?"

"Better," she replies, "forty times better, my banner than my sword."

In 1431, during a time known today as the Lancastrian War, the third of the Hundred Years' War, Joan of Arc was executed, burned at the stake. Almost 500 years later in 1920, Pope Benedict XV canonized her, and a statue of Joan of Arc stands today in the Notre Dame cathedral in Paris.

While it would be easy to take these stories at face value and put a neat little bow on the history of how France got the white color, it just may derive from a much more practical use – a use, as we often see in the true history of flags – in war. And sadly, this use derived after a horrible incident of friendly fire during the Battle of Fluerus.

The Battle of Fleurus in July of 1690 was a battle in the Nine Years' War, fought between the French and the coalition of European powers led by the Holy Roman Empire. By the late 17th Century, as was their military tradition, every regiment of the French army carried its own flag. And, as you can imagine, this confusion of whose flag belonged to whom, led to tragic results. In the fog of war, two French regiments carrying two separate flags, confused each other for the enemy and attacked one another in a quick and bloody skirmish, leaving several French soldiers dead – killed at the hands of their own men. Lucky for the French but unlucky for the many men who died in vain, this incident of friendly fire hardly impacted the results of the battle, which ended in a resounding French victory. It did, however, leave a lasting scar in the memory of those who survived and lead to the habit of attaching white scarves – the color of the Bourbons – to the regimental flags, in an effort to keep this from ever happening again. Therefore, this practical addition of the royal color to their military flags is at least one reason why the color white became a permanent fixture on the flags of France ever since.

Wait a minute – so, where did the white come from? Was it to symbolize the French devotion to the Virgin Mary? Was it in honor of the valiant heroine, Joan of Arc, and her battle flag against the English? Or was it simply adopted by the military regiments in a way to standardize their flags with the color of the Bourbons, so they would stop killing each other on the battlefield? Well, the answer is yes. And yes. And yes. These are all reasonable, historically correct origins of the white color on the French flag. You see, these colors can hold different meanings at the same time. Remember as I said, it just depends on who you ask – and more importantly, when you ask it.

So, there you have it. These are the historical narratives of how and why these three colors came to represent France. But how did these colors come together to become the modern flag? Well, that is a story unto itself, and we'll jump ahead a few hundred years to the French Revolution and its Tricolour right after the break.

BREAK

Liberté, égalité, fraternité: The official tripartite motto of France – Liberty, Equality, Fraternity – is attributed to the French lawyer and statesman Maximilien Robespierre, easily one of the best-known figures of the French Revolution. Fun fact: This tripartite motto is in the form of a powerful linguistic figure of speech used for emphasis called a hendiatris, in which three words are used to express a singular idea. Forgive me, I'm a copywriter by trade, so that little fun fact is for myself.

Robespierre spoke these three famous words during a speech on December 5, 1790, regarding the organization of a National Guard – that is, a commoner's police force that operates outside the royal army – in order to defend and maintain the very ideals that he and many others just fought for: their liberty, their equality, and their national fraternity. Robespierre said, "On their uniforms engraved these words: FRENCH PEOPLE, & below: LIBERTY, EQUALITY, FRATERNITY. The same words are inscribed on flags that bear the three colors of the nation."

By December 1790, the French Revolution was in full swing. One year prior, on July 14, 1789, a civilian insurgency, an insurgency that would become this National Guard, stormed the Bastille in Paris – a revolutionary act against a potent symbol of the monarchy's abuse of power. While this was an act of rebellion against the monarchy and King Louis XVI's despotic reign, the goal did not begin as a means to end the monarchy outright – and their choice of colors proves this. The day before the assault, July 13, a group of Parisian statesmen agreed to form a "bourgeois militia," or a "citizens militia," to restore order as royal power in Paris waned. The cockades, or ribbons, worn by this militia was first agreed to be the centuries-old colors of Paris – red and blue. A member of this group was the famous Marquis de Lafayette, the French military officer who fought alongside the Americans in their Revolutionary War against England – remember that, because he will be important soon. It was Lafayette and who insisted on adding a band of white to the cockade, which, as you know, was the color of the king and the Bourbon Dynasty. Named the "colors of freedom," this blue, white, and red cockade was presented to Louis XVI by Paris Mayor Bailly when the king came to visit the city on July 17, following the siege of the Bastille. Soon after, these "colors of freedom," the revolutionary colors, were formally adopted by the National Guard on July 31.

While revolutionary fervor was gripping Paris, the initial goal of the militia was not to end the monarchy, as the white band shows, but to the rein in the king's corruption, and of course, his wife Marie Antoinette's reckless spending and devastating financial whimsy. To stress that point even clearer, there's an anecdote from October 1, 1789, when a mob sympathetic to the National Guard stormed the royal palace in Versailles. They did not do this depose the monarchy outright, but to bring the king and his family to Paris, and make him more accountable to the people through a parliamentary, constitutional monarchy led by the National Assembly. But of course, that idea didn't last too long, and the Revolution took his head a few years later in 1793.

The mid-16th to mid-18th Centuries are known today as the Age of Sail. This was a time across the world when those who controlled the seas dominated international trade, politics, and of course, warfare. And the French were no different – in fact, they excelled. During the Revolution, which in 1789 was at the pinnacle of this age, the lower-class sailors came close to mutiny in order to fly the Tricolour in direct defiance of their aristocratic officers and their royal naval flag, which was a white Bourbon cross on a royal blue ground. In a speech to the National Assembly in 1790, Honoré Gabriel Riqueti – a nobleman turned revolutionary known as the comte de Mirabeau – proclaimed, "No, my fellow deputies, the Tricolour will sail the seas; earn the respect of all countries, and strike terror in the hearts of conspirators and tyrants!" And from then until the fall of Napoleon – which we'll discuss shortly – the French naval flags adopted the blue, white, and red colors of freedom.

Now let's get back to Marquis de Lafayette, who I told you to remember from the bourgeois militia, the National Guard. I bring up the importance of Lafayette not only because of his central role in the story of the French Revolution and his part in establishing the colors on the cockades that became the Tricolour, but because of his involvement in the American Revolution, and how the red, white, and blue of the American flag may have directly influenced that of France. It is safe to say that his addition of white to the red-and-blue cockade had multiple motives. The first, as I just mentioned with an anecdote earlier, was to ease the minds of the king and his loyalists about the true intentions of the National Guard. The second motive, consciously or not, is believed to have taken root during his time in the American Revolution. Lafayette is not only a hero of the French Revolution, but a hero here in America as well, with towns, streets, and schools named after him to this very day. And back in France, it was Lafayette who was instrumental in crafting the Declaration of the Rights of Man, which was published by the French National Assembly in 1789. This document was framed after the United States Declaration of Independence and Constitution, and was written in direct coordination with none other than his friend and colleague, Thomas Jefferson, the author of those American documents. Therefore, in the mind of Lafayette, it can be surmised that the red, white, and blue of the American flag were the most potent symbols of a revolution against a tyrant king. In other words, his second motive for adding white to the red and blue could very well have been directly inspired by the colors of the American flag and the republic for which it stands.

Where did the Tricolour come from? Was it from Robespierre's National Guard, with the white band to represent the king they came to overthrow? Was it to symbolize the tripartite motto of liberty, equality, and fraternity? Or was it inspired directly by the American flag and that nation's successful revolution against their own tyrant king? And again, the answers are yes, yes, and yes. And yes, to even more origins that we have not discussed, like the idea that it symbolizes the people's control over the monarchy, with the two colors of Paris squeezing the Bourbon royal white from both sides. The answer is yes, because, as I said before, the colors of the French flag did, can, and do mean different things – even competing things – all at the same time. It just depends on who you ask and when you ask it.

Coming up after the break, we're going to discuss the rise of the Tricolour as the national flag of the First French Republic, and its Reign of Terror under the leadership of Maximillian Robsepierre.

BREAK

In 1791, the National Assembly adopted the constitution, stripping much of the power from the king and giving it to the people. Lafayette's Declaration of the Rights of Man became its preamble, guaranteeing the rights of free speech, freedom of the press, freedom of religion, and more to all active French citizens – but of course, this being 1791, these freedoms didn't apply to women or the poor. Sorry, ladies. Finally, on September 21, 1792, the National Assembly voted to abolish the monarchy, and the First French Republic was born the very next day – and by 1794, the Tricolour became the national flag of the new revolutionary France.

On January 21, 1793, the revolution took King Louis XVI's head by guillotine, one day after he was found guilty of treason for his counter-revolutionary conspiracies with foreign governments that sympathetic to the crown. If you thought St. Denis's beheading brought red into the flag, the Revolution would soon drown it in the blood of nearly 30,000 French citizens.

1793 was a hallmark year for the French Revolution. The monarchy had been reduced to memory, Louis XVI was without his head, and France was plagued with war – both in Austria and civil war at home. To quell the daily fears of violence and foreign invasion, the Committee of Public Safety – an ironic name for what they were about to do – was formed as a de facto war council to oversee this two-front war, as well as to temporarily fill the vacant seat of the executive of the National Convention. Who was the former executive, you may ask? Well, that was King Louis XVI, who they had conveniently just executed. The Committee of Public Safety – an ironic name for what they were about to do – soon rose to power and took near-dictatorial control over the new France.

Within just a few short months, the Committee became dominated by anti-aristocratic radicals, hell-bent on rooting out enemies of the revolution and swiftly leading the accused to the guillotine, often without trial. After a quick accumulation of power through a variety of electoral, legislative, and strongarm tactics that we won't get into on this show, Maximilien Robespierre – Mr. Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity himself – emerged as the leader of this radical, paranoid, and extremely violent Committee of Public Safety. On September 5, 1793, Robespierre declared that terror was to be"the order of the day," and the tri-color flag that first emerged as an icon of freedom against tyranny quickly became a symbol of violent retribution against the perceived enemies of the Revolution.

The next month, on October 16, Marie Antoinette is executed by guillotine, and heads begin to roll on a daily basis. By December, most of France's churches are closed in the name of secularism, and on Christmas, Robespierre declared that the constitutional government was effectively suspended until his war against the "enemies of liberty" was won. Civil liberties were canned. The Declaration of the Rights of Man, abandoned. Neighbor spied on neighbor, son on father, and sister on sister. Any utterance heard that was critical of the revolution or its leadership was quickly silenced by the guillotine, because, in the words of Robespierre, "Softness to these traitors will destroy us all." In the span of nine months, nearly 30,000 people – ordinary people, hardly all aristocrats or counter-revolutionaries – were executed. As history has often seen with absolute power, Robespierre's reign corrupted him absolutely. On July 26, he gave a fiery speech to the convention, railing against his enemies, citing bizarre conspiracies, and, while not giving their names publicly, proclaimed that there were traitors among them in that very room. Fearful that they themselves would be accused next, the National Convention decided that they had had enough. On July 27, Robespierre was declared an outlaw, arrested, and charged with crimes against the republic. The very next day, getting a taste of his own punishment of choice, Robespierre and twenty-one of his associates were sent to the guillotine without trial. And as his head fell, so did the Reign of Terror.

After being cast under the dark cloud of terror, the Tricolour would once again represent the ideals of the French Republic – and would soon fly over much of the continent during the French Empire under Napoleon Bonaparte. For this episode's purposes, we're not going to go into the story of Napoleon and the First French Empire. But rest assured, we'll make time for him later on in this series, especially if we cover the Italian tricolor flag, which he directly influenced during his reign as the King of Italy. To learn more about Napoleon's empire, I again recommend that you listen to season 3, episode 54, of the Revolutions Podcast – I'll leave a link for you in the show notes.

Like I said, the Tricolour was used as the flag of the First French Empire under Napoleon. But, for better or worse, its days were numbered. In 1812, Napoleon's defeat and his failed conquest of Russia was a death blow to the French Empire. While the imperial army was left licking its wounds, a coalition of European powers allied against Napoleon, ultimately reducing the empire back to France's natural boundaries, and in 1814, he was forced to abdicate the throne. By 1815, the empire was gone. The once-revolutionary French Republic was no more. In its place was the old Bourbon Dynasty, back from exile by order of the European Coalition. And the Tricolour – the messy blue-white-and-red colors of freedom – were bleached and scrubbed away, replaced by the white flag of royalty, which was raised again over the newly restored Kingdom of France.

The years 1815 to 1830 are known to French history as the Bourbon Restoration, that is, the restoration of the old monarchy. Although the kingdom was restored and the Tricolour replaced, the new government was unable to reverse many of the very popular and publicly lauded republican traditions of the French Revolution. Thus, this kingdom was a constitutional monarchy – not an absolute one – with the king as its supreme head of state, and the parliament elected, more or less, by the people. That said, a pesky little constitution wasn't going to get in the way of the aristocrat's revenge on the old revolutionaries.

When Louis XVI's brother, Louis XVIII, came to power, the ultra-royalists decided that it was time to get even for everything they lost, and every indignity suffered during the Revolution, the Republic, and Napoleon's reign. Terror gripped the land once again. Aptly named after the white royal flag, The White Terror of 1815 was a string of mass arrests, government and military purges, mob lynching, exiles, and hundreds of executions, targeting anyone who was suspected of loyalties to the previous governments. The people were put on notice.

Louis XVIII died in 1824, succeeded by his younger brother, King Charles X. Charles pursued a more conservative agenda than his brother, and sought to grant even more power to the throne and to the Church while simultaneously limiting the freedoms of speech, press, elections, and more. But in the summer of 1830, parliamentary elections proved unfavorable to the royalist coalition. So, on July 6, the king suspended the constitution, and on July 25, he issued ordinances that dissolved the parliament, censored the press, hindered voting rights, and called for a new election to override the previous one. Seriously, Charles? If history should have taught him anything, it's that the French people have a tireless appetite for revolution – and a newfound tradition of taking royal heads. Therefore, these ordinances would be the last act of the Bourbon Regime. As they did in 1789, the people rose up against the monarchy in a popular revolt, and on July 31, after the fall and desertion of much of the military, the Parisians prepared their forces to storm the king's palace. As the mob grew and gathered outside the gates, and as the memory of his eldest brother's execution lingered soberly in his mind, Charles decided that he would feel much better with his head connected to his neck, and he fled with his family in exile to England. On August 2, King Charles X abdicated his throne, and the white flag of the Bourbons was lowered for the last time. The Tricolour took its rightful place with the coronation of the citizen-king Louis-Philippe and has remained the flag of France ever since.

This is clearly not the end of the story of the French, nor of the successive French revolutions, wars, empires, and republics that raged and waned for the next 110 years, from the Revolution of 1848 to the reign of Napoleon III to the occupation of France by the Nazis in WW2. But for the most part, except for those four dark years under the iron heel of the German Swastika flag – which we will cover on another episode – this is, for our purposes, the end of the story of the Tricolour.

Red is for the blood of St Denis and the martyrs who carried the Oriflamme, and those who fought valiantly against tyranny; Blue is for the France Modern with its fleur de lis, the ancient kingdom, and the miraculous blue cloak of St. Martin; and white is for the Virgin Mary, for Joan of Arc, for distinguishing France in battle, and of course, for the Bourbon Dynasty, once and for all reduced to history, but essential to French history, nonetheless. These colors are for all of them. Or none of them. I guess it just depends on who you ask, and more importantly, when you ask it.

That's it for this episode of why the flag. You can read show notes at flagpodcast.com and follow us on Instagram @flagpod. And make sure you subscribe to this show on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, Stitcher, and wherever you get your podcasts.